January 31, 2018 — Paris, France

The recent thaw in Israeli-Saudi relations must be understood in the context of the lengthy Saudi Arabia-Iran cold war, and, more generally, the larger conflict between Sunnis and Shi’ites. Four rivalries drive a wedge between Riyadh and Tehran:

Religious rivalry: The Saudi kingdom fears a political reawakening of the Shi’ite religious minority. Shi’ism is tolerated as an unfortunate departure from the norm at best and a heretical sect to be eradicated at worst. From this perspective, Israel is plainly a Jewish state…of the Sunni variety!

Cultural Rivalry: Though often unacknowledged because it goes against the brotherhood principle of the umma, the worldwide community of Muslim believers, defiance and hostilities have often prevailed on both sides of the Gulf, the Arabian and the Persian.

Economic Rivalry: Before the Islamic Revolution of 1979, Iran was the third-largest producer of oil in the world and Saudi Arabia the largest. Once economic sanctions—which have hit the oil sector particularly hard—are lifted, Tehran will once again become a fierce competitor, exporting vast amounts of its abundant natural gas. It’s worth recalling that one of the most significant reasons for plummeting crude oil prices two years ago was Riyadh’s export of oil in bulk, which destroyed a core sector of the Iranian economy just as it was on the road to recovery.

Institutional Rivalry: On one side, a feudal Bedouin monarchy, on the other an Islamic Republic headed by a government that, in principle, consists of a government with several branches and a balance of power between them. In truth, both are authoritarian regimes, with each competing to be the model for the Muslim community worldwide.

More broadly, Iran’s hegemonic expansion (the Islamic Republic and its militias or supporting groups are waging wars in Yemen, Syria, Iraq, destabilizing the entire region) and its efforts to become a nuclear power greatly concern Saudi Arabia and Israel, and also worry the West.

In light of these issues, not only does Israel fade into the background of the (supposed) concerns of Arab States as an “oppressor of their Palestinian brothers,” but Israel can even be accepted as an ally, insofar as it also opposes the territorial expansion of Iran in Lebanon (Hezbollah) and in southern Syria. The Iranian regime, in vilifying Israel, claims to be advocating the Palestinian cause.

Israel sees much to gain. Isolated in the heart of a hostile Arab region, and, more broadly, a Middle East where it has no real ally, the Jewish state has always been receptive to any opening for regional diplomacy, and Saudi Arabia is an opportune partner.

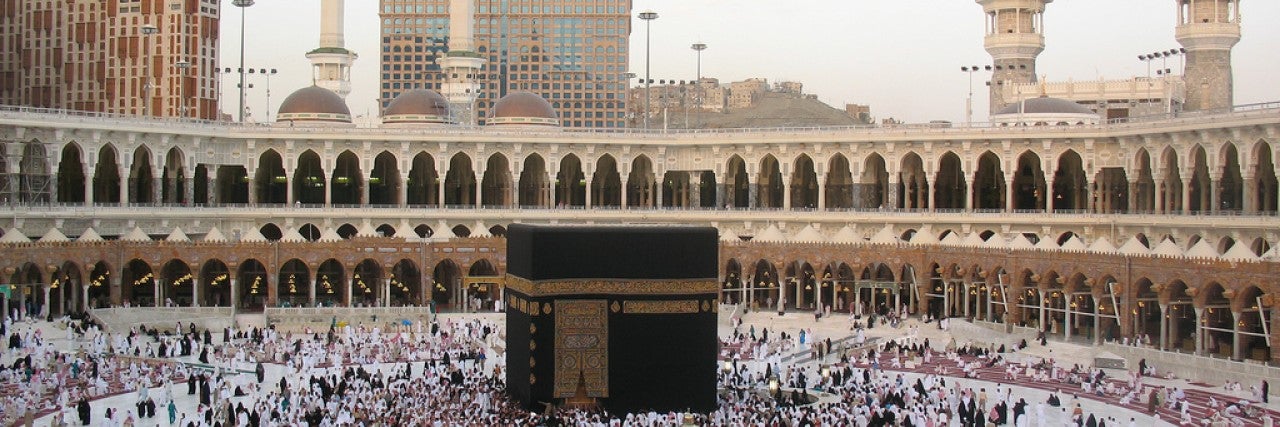

But what exactly is the Saudi motivation? It is surely not acceptance of Zionism. Rather, it is the old truth that the (secondary) enemy of my (main) enemy is my friend. Riyadh will get the support of one of the mightiest military powers in the region, and thus be able to counter Iran—which threatens it on several fronts. Therefore, the Saudi regime, one of the world’s most rigorous manifestations of political Islam, will try to convince its citizens—and more than 1.3 billion Muslims the Sunni world over—that in the end, perhaps the “Zionist Entity” isn’t quite as dangerous as they had once believed…

Donald Trump’s declaration recognizing Jerusalem as the capital of Israel will do nothing to change this paradigm. Riyadh’s criticism of Trump’s decision was mere lip service, not followed by any concrete retaliatory measures—and for good reason. Didn't a Saudi dignitary recently proclaim that “Riyadh is more valuable than Jerusalem?” With the Saudi capital currently under ballistic missile fire from pro-Iranian militants in Yemen, we can certainly understand such statements…

Beyond rhetoric, what will the new partnership between Saudi Arabia and Israel look like?

First, Saudi Arabia has asked for and been granted access to Israeli intelligence. Intelligence, a Saudi weak point, is an Israeli strength…The feeling of being surrounded by Shi’ite forces—Iran to the east, Iraq to the northeast, the Hasa Plain directly to the east of the Saudi kingdom itself, Yemen to the south, Hezbollah (not as close but rather powerful) in Lebanon, etc. Is this not similar to the situation faced for decades by…Israel? True, Saudi Arabia isn’t under threat of invasion as was Israel until at least 1973, but what matters isn’t necessarily the actual geostrategic reality on the ground, but the perception of it.

Second, Israeli influence in Washington is a hot commodity in the relentless Saudi struggle against the Iranian nuclear accord signed on July 14, 2015. Israelis and Saudis agree on this issue. However, the Israeli side has received an express delivery of state-of-the-art F35 fighter planes, whereas the Saudis have come up empty-handed. Furthermore, if Iran ever did decide to strike the Jewish State, Israel’s response would be apocalyptic, whereas a strike against Saudi Arabia would subject Iran to what we can assume would amount to a mere scolding, given the disastrous war Riyadh is waging in Yemen—a quintessential example of Saudi military weakness and inefficiency. Except, of course, that the Saudis would look to the United States, a traditional ally since 1945, for defense aid. In such a situation, support from friends of Israel in America could prove decisive. That is why in Washington, we see even more Saudi than Israeli lobbying.

Thus we see, at least in the short term, the Mullah’s pan-Shi’ite Iran and its “international brigades” in Asia (Afghanistan, Pakistan, etc.) on one side, the Sunni Arab world on the other, and the United States and Israel firmly planted in the second camp. In Saudi Arabia, young Prince Mohamed Bin Salman has recently shown a certain willingness to modernize Saudi society (he stripped the religious police of their power to arrest, broke the decades-old taboo against women driving, etc.). But are these measures and the anti-corruption crackdown that he has recently undertaken sustainable? The Saudi regime is inherently vulnerable. At the same time, however, the Islamic Republic’s ability to stay in power is also questionable (it almost fell in 2009), as is the future of Hezbollah in Lebanon and the potential for peace in Syria. The instability of both the Saudi and Iranian states should make us wary of drawing long-term conclusions about alliances in the region.

If there are positive changes in the Shi’ite camp in the coming years, what plan of action might Israel adopt? Would it still be worthwhile for Saudi Arabia (which has a viscerally anti-Israel population) to take sides in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict? Sooner or later, we will have to confront these issues... We’d best address them before the next crisis hits...

Frédéric Encel is a professor of international relations at Sciences Po, the Paris Business School, and the School of Administration (ENA). He holds a doctorate in geopolitics and is a renowned author and scholar on the Middle East.