July 18, 2019 — Brussels, Belgium

This piece originally appeared in New Europe.

By Michael Sieveking

If Europe is serious about combating antisemitism, the Lebanon-based global terror group Hezbollah must be stopped in its tracks. As we marked on 18 July the seventh anniversary of the suicide bombing in Burgas, Bulgaria, we remember the lives of five Israeli tourists and a Bulgarian Muslim bus driver that Iran’s most-deadly proxy violently cut short on that fateful day.

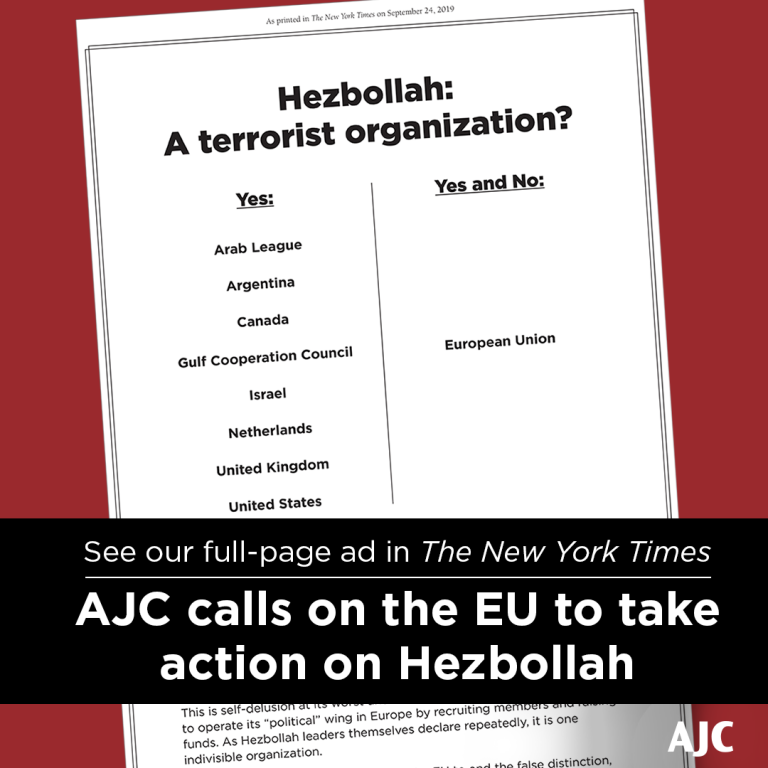

The EU, after nearly a year of deliberation, reacted to an atrocity that was carried out in one of its own member states by proscribing in 2013 Hezbollah’s ‘military’ but not its ‘political’ wing. The artificial distinction was a proverbial EU compromise where it’s a good deal as long as nobody is happy with it. Except – mind you – the terror group’s masters in Tehran who had literally gotten away with murdering Jews on European soil.

The deadly 2012 attack in Burgas was a clear case that should have moved the EU to add to its terror list Hezbollah in its entirety. Astonishingly, to this day, it hasn’t happened. The partial ban raises serious questions about the bloc’s resolve to fight terrorism on European soil and protect its Jewish communities.

In Germany alone, an estimated 1,050 Hezbollah members are active, according to Berlin’s federal intelligence service report for 2018. Currently, the group can freely raise funds and recruit new members supposedly in support of its so-called political or charity work. Designating Hezbollah in its entirety under EU Common Position 931 would allow the bloc to at least freeze assets.

As The Daily Telegraph reported last month, British intelligence in 2015 caught a Hezbollah terrorist stockpiling in London some three tonnes of the chemical compound ammonium nitrate that can be converted into an explosive. This was more than was used in the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing that killed 168 people. That same year, authorities in Cyprus apprehended Hezbollah member Hussein Bassam Abdallah with nine tonnes of ammonium nitrate.

Abdallah later confessed to plotting terror attacks on Jewish and Israeli sites in Cyprus.

Hezbollah, spawned and nurtured by Iran, as well as the regime’s Quds Force, pose a clear and present danger specifically to Jewish communities in Europe. The 2019 intelligence report of Germany’s most populous state, North Rhine-Westphalia, revealed that Iranian agents are spying on Jewish sites as potential terror targets. Last year, German police raided several homes of Iranian operatives and reportedly collected information on possible targets, including a Jewish kindergarten.

One of Hezbollah’s most notorious acts of terror occurred 18 years to the day before the Burgas attack when the AMIA Jewish community centre in Buenos Aires was destroyed by a bomb, killing 85 people, including Jews and non-Jews ranging in age from 5 to 73. Another 300 were injured.

An investigation by the Argentine government concluded that Iran and Hezbollah were directly involved, but 25 years after the attack no one has been brought to justice.

What’s more, Hezbollah is a major purveyor of anti-Jewish hatred in Europe. At the annual ‘Al Quds’ marches, Hezbollah flags are front and centre, antisemitic chants are commonplace, and banners with Stars of David are burned. Josef Schuster, head of the German Central Council of Jews, said that the ‘Al Quds’ demonstrations “transport nothing but antisemitism and hatred of Israel.” Ahead of this past May’s march in Berlin, Germany’s antisemitism envoy Felix Klein even urged citizens to don a kippah in solidarity with the Jewish community.

Europe’s closest Western partners across the Atlantic, the US and Canada, have long designated the group as a terrorist organisation. Earlier this year the UK followed suit and The Netherlands added Hezbollah to its list of terrorists in 2004. Speaking about the UK’s decision to list the group alongside other Islamist terror groups like Hamas, ISIS, and al-Qaeda, British Home Secretary Sajid Javid called the distinction between Hezbollah’s two factions mere “smoke and mirrors.”

It’s often contended that blacklisting Hezbollah will hamper Europe’s ties with Lebanon. There is no evidence, however, that a sensible counter-terrorism policy targeting Hezbollah could not be harmonised with robust bilateral ties with Beirut.

Strong US-Lebanon relations are a case in point – the same goes for Canada, The Netherlands, and the UK. This is not to speak of the demoralising message Europe sends with its partial ban to the many moderates in Lebanon who are trying to marginalise Hezbollah extremists.

To the EU’s credit, it has come a long way in addressing the resurgence of antisemitism. Triggered in part by the Brussels Jewish Museum shooting on 24 May 2014, the bloc appointed within a year a special coordinator. On 6 December 2018, the EU’s Justice and Home Affairs Ministers issued a historic declaration on the protection of Jewish life, which the European Council echoed weeks later.

Why then – with all this good on display – is Europe still AWOL when Hezbollah, a state-sponsored antisemitic and genocidal terror group, is glaring at it down the barrel? We’re left with the horrifying prospect that it’ll take another deadly Hezbollah attack for the EU to act.

The unfinished business on Hezbollah is today Europe’s fight against antisemitism writ large.

Next year all eyes will be on the EU Presidency of Germany, a hotbed of Hezbollah activity, and whose Jewish community has long pleaded with its government to act on the threat. Foreign Minister Heiko Maas said that his country intends to prioritise the fight against antisemitism. A recent EU survey showed that 40% of young Jews are considering emigrating. However, if Germany took the lead in Europe on banning Hezbollah in its entirety, others would surely follow.

Confronting this growing threat to Jewish life in Europe is nothing short of a moral responsibility.

Michael Sieveking is Deputy Director of the AJC Transatlantic Institute.