May 5, 2020

By Bjorn Okholm Skaarup

“I was appointed as chief prosecutor in what turned out to be the biggest murder trial in human history. I was 27 years old,” says Ben Ferencz, the last surviving prosecutor of the Nuremberg Trials. “It was my first case. I had never been in a courtroom before.” More than 70 years after overseeing the Einsatzgruppen Trial, Ferencz, who just turned 100, continues his commitment to justice.

This past January, Ferencz wrote an op-ed in The New York Times following the killing of Iranian general Qasem Soleimani. “I am pretty embarrassed to find the president of the United States being involved in what seems to me to be an act of murder, and also quite annoyed that he tried to conceal it by saying the victim was taken out,” he says. “What do you mean, taken out? Taken out for a walk? Taken out for a beer? Only certain kinds of self-defense are permissible, when the danger is so instantaneous and certain that you must respond. That was not the condition here.” The centenarian champion of law and concord has been an eyewitness to a turbulent century that saw a near collapse of human civilization followed by significant progress in international cooperation and the rule of law. His long memory and wry wit offer a unique perspective on past and present, which he shares freely from his home in Florida.

Young Benjamin arrived on Ellis Island as a ten-month-old Jewish immigrant from Transylvania in 1921, only 35 years after the unveiling of the Statue of Liberty. Despite his humble background, after graduating from the City College of New York the gifted young man attended Harvard Law School, graduating in 1943. Serving in Patton´s Third Army during World War II, he established its pioneering war crimes section, which helped pave the way for the Nuremberg Tribunal.

After the war, Ferencz was put in charge of a 50-man team appointed to collect evidence for the subsequent trials of the German doctors, judges, industrialists, and others charged with war crimes. In early 1947, one of Ferencz's assistants discovered a file of nearly 200 reports from the Einsatzgruppen (action groups), listing their murderous activities in 1941-42. The evidence showed how these mobile killing squads operating in occupied Soviet territory had launched the genocide of Europe's Jews even before the death camps were built. Telford Taylor, who took over the direction of the Nuremberg Tribunal from Robert Jackson, was initially skeptical when Ferencz demanded a new trial of the killers based on those discoveries. Public interest in Nazi war crimes was waning, and the Pentagon had already approved staff and budgets for the trials Taylor had under way. Ferencz recalls telling him, “You have to put on a new trial. This is outrageous. I have a million dead people here in my hands. You are not going to let these murderers go.” Taylor asked, “Can you do it in addition to your other work?” He replied, “Sure,” and Taylor said, “You’re it.”’ The defendants were hand-picked and highly educated SS, SD and Gestapo officials, far from the “ordinary men” who have often been the focus of Täterforschung, the academic study of Nazi perpetrators. Among them was a former priest, an opera singer, an architect, and many academics with law degrees. A quarter of the defendants held PhDs (Otto Rasch, head of Einsatzgruppe C, held two), and one was a former dean at the Humboldt University in Berlin.

The Nuremberg Tribunal that documented the darkest chapter in European history was one of the proudest moments in American legal history. Though time-consuming and costly, the trials performed a great service to posterity by exposing the moral collapse of a highly developed society. And by dedicating the ninth of the twelve subsequent Nuremberg trials to the Einsatzgruppen, Ferencz ensured that at least one would focus on the Nazi genocide of European Jewry.

The charges against the defendants were presented on September 29-30, 1947, exactly six years after the Babi Yar massacre of Kiev's Jews. That unparalleled two-day mass murder of 33,711 men, women, and children (according to the murderers' own figures) was the most extensive of the Einsatzgruppen massacres. The two responsible SS commanders, Dr. Dr. Otto Rasch and the former architect Paul Blobel, both sat in the dock, although the case against Rasch was abandoned for health reasons, and he died the following year. The executioners’ detailed reports of their mass killings listed the locations and number of victims, as well as the units involved and their commanding officers. Although some survivors and eyewitnesses of the Einsatzgruppen massacres testified in other trials, providing some of the most moving and harrowing testimony, Ferencz decided not to call any witnesses because the perpetrators’ own paper trail was so damning. “I never regretted that, because I could have had a thousand witnesses,” he explains. “I said, ‘I will judge the defendants only on their own record, top state-written Geheimsachen of Germany.” He spent just two days presenting the case for the prosecution, while the defense was drawn out over 136 days, much to his frustration.

In March 1948, a month before the conclusion of the trial, Ferencz, Taylor, and their wives were flying back from Berlin to Nuremberg in an old propeller aircraft when the plane suddenly lost altitude and all passengers were ordered to evacuate. Over seventy years later, Ferencz still recalls this near-death experience 3,000 feet over Berlin. “The pilot was handing out parachutes, we were six people, I think, who jumped,” he remembers. “I was the first next to the door, and I tried to open it, but I couldn’t because the wind pressure was blowing it back. I got my leg in the door, and my knee, and suddenly it opened, and I fell out. I then pulled the rip cord. They had told me to count to ten. I counted, ‘1…2…10!’ Then, I saw below me the ruins of Berlin.” Luckily, everyone survived and were able to hear the verdict on the 22 SS men charged with the murder of more than a million civilians. All were found guilty—14 sentenced to death and the rest sent to prison. Some of the condemned men protested loudly, as Ferencz remembers vividly: “I knew that some of the worst ones didn’t get sentenced to death. And I knew that because we had microphones – and this is first news here – we had a microphone planted in their cells. We would hear the conversations between them, and they would say, ‘Oh did you see that dog so-and-so? He was a real bloodhound and he got off with 20 years!”’

During the trial, chief defendant Otto Ohlendorf, former commander of Einsatzgruppe D, corroborated the accuracy of his reports of more than 90,000 liquidations. Erich Naumann, who headed Einsatzgruppe B, put a legal noose around his neck during Ferencz’s cross-examination by showing no remorse about his unit’s mass shootings and use of gas vans, and later defending the annihilation of the Jews as “a necessary war aim.” Ohlendorf’s subordinate, Werner Braune, responsible for the December 1941 “Christmas Massacre” of 14,000 Crimean Jews, similarly held to his view of Jews as malevolent carriers of Bolshevik ideology. The former architect Paul Blobel, who would become a chief architect of the Nazi Final Solution through its many stages of radicalization, was the first to order mass exterminations of Jewish children, having his Sonderkommando 4a carry them out only a month before organizing the Babi Yar massacre. Blobel later commanded the infamous Sonderaktion 1005, which tried to cover the tracks of the countless Einsatzgruppen massacres by reopening the mass graves and burning the bodies, a ghastly operation that continued until the end of the war. These four key defendants were hanged in June 1951, while nine of the other condemned men had their death sentences commuted to imprisonment.

This demonstration of leniency followed an intensive campaign led by West Germany’s first Chancellor, Konrad Adenauer, which was ultimately supported by John McCloy, the American High Commissioner for Occupied Germany. All the remaining Einsatzgruppen defendants were released between 1951-58, and so were industrialists from Krupp and IG Farben who had abetted Nazi crimes. According to Ferencz, McCloy later regretted this. After reading Ferencz’s book Less Than Slaves (1979), on Nazi atrocities and use of slave labor, McCloy contacted Ferencz. “He wrote to me, ‘If I had known all that before, I might have acted differently’” remembers Ferencz. “It was not an apology, but it was a recognition that he had perhaps gone too far.” The decision to go easy on the Germans, Ferencz believes, was a political gesture by the U.S. General Patton, he notes, “who was my commander during the war, said in a speech in London, while the war was still on, ‘We should be fighting the real enemy, the Russians and not the Germans,’ and the result? We were more lenient than I would have been.”

While disagreeing with them over this, Ferencz collaborated successfully with McCloy and Adenauer on the first German reparations program for Holocaust survivors. Chancellor Adenauer, incidentally, used Ferencz’s pen to sign the historic 1952 agreement between Israel and Germany that has paid almost $100 billion in compensation. As head of the Jewish Restitution Successor Organization (JRSO) beginning in 1948, Ferencz stayed eight more years in Nuremberg, where his 4 children were born. He considers this work as his crowning achievement. “There is no victim of Nazi persecution who has not become a direct beneficiary, Jews and non-Jews alike, of the work I did for the restitution programs,” he says. “That is the proudest period of my life.” He later obtained compensation for Polish female victims of medical experiments at the Ravensbrück concentration camp, despite German opposition to compensating victims living behind the Iron Curtain. “They said I was just a Communist trying to embarrass the German government, trying to enrich myself,” he says.

Just as Ferencz was departing Germany, the last of the condemned Einsatzgruppen defendants (including Martin Sandberger and Walter Blume, both JD-PhDs, whose detailed murder reports had declared first Estonia and later Greece judenfrei) were released from Landsberg Prison, against his protest. Sandberger lived as a free man for more than half a century before dying in 2010, while Blume left a veritable Nazi treasure to his relatives, recovered in 1997, that included gold teeth and gold bars, jewelry, and luxury watches, with an estimated value of $4 million. Ferencz says, “Everything that undermines the rule of law is dangerous. And these men, they may have been gentlemen to their cats and dogs, but they were responsible for killing thousands of little children, one shot at a time. I don’t have much mercy in my heart for them, I must say.”

After Nuremburg, Ferencz continued his pursuit of justice, becoming a driving force in the establishment of the International Criminal Court (ICC). When the first ICC trials were held for crimes against humanity (2009-11) the then 91-year-old Ferencz gave one of the closing statements for the prosecution. At the UN, he is known as “Mr. Aggression,” and has for decades tried to push the institution to agree on a universal definition and condemnation of aggression. He emphasizes that “nobody can fire me, because nobody hired me!” His long-term goal is passage of a resolution that criminalizes armed conflict, “for war makes mass murderers out of otherwise decent people.”

Ferencz, who arrived in the United States during Woodrow Wilson’s presidency, regrets growing American indifference to the rules-based international order and institutions that the U.S. was itself instrumental in establishing. In contrast to Presidents Roosevelt and Truman, who set up tribunals to prosecute war crimes, their current successor in the White House recently pardoned and invited a convicted war criminal, and subsequently threatened another country with the textbook war crime of striking its cultural sites. “We have to change our hearts and minds,” says Ferencz. Commenting on his New York Times op-ed, he insists: “People have to recognize that compromise is not cowardice and seeing the other fellow’s point of view is necessary. I have seen the horrors of war first-hand. Perhaps more than any man still alive. And I know that law is always better than war.” In the wake of the Einsatzgruppen Trials, Ferencz has expressed particular opposition to the notion of anticipatory self-defense, which his chief defendant, Otto Ohlendorf, repeatedly invoked to justify his mass killings, and which was recently used to defend the drone attack on Soleimani. “We may say he is a very bad man, and I can’t judge that. I don’t reach any such conclusion, until I put the man on trial and give him a chance to defend himself. That’s the way to do it. I did exactly that with Mr. Ohlendorf. He had plenty of time to issue his defense. I, as an American responsible for his death, I am particularly sensitive, when I see people of our own government doing things which are strikingly similar. All I can do, I am a hundred years old now, is to raise my voice in opposition.”

Asked about his milestone birthday, Ferencz laughs. “I don’t pay any attention to that. I was afraid they were going to interrupt my work and celebrate me for one reason or another. It’s not my fault I’m still here! I have a job to do! People say, ‘When are you going to retire?’ Retire to do what? Go and play golf? See if I can put a ball in a hole? I quit that when I was five years old! It seems to me such ridiculous things that normal people do, so they don’t appeal to me. I have to work!”

A role model over his long career has been the Danish Renaissance astronomer Tycho Brahe. “He was once asked why he had spent so much time watching the sky, and he answered, ‘I have here 97 books each charting the exact movement of the stars. I have built an observatory, and these are absolutely correct.’ Maybe I can get to 100 charts. And someday, perhaps someone will look at them, and I will have saved that person 25 years of labor. When the Americans landed on the moon, they had with them the tables of Tycho. He has given me the courage not to be discouraged, and I keep going, every day, 365 days of the year. My slogan is ‘Law, not War!’ And my answer is always, ‘Never give up, never give up, never give up!”’

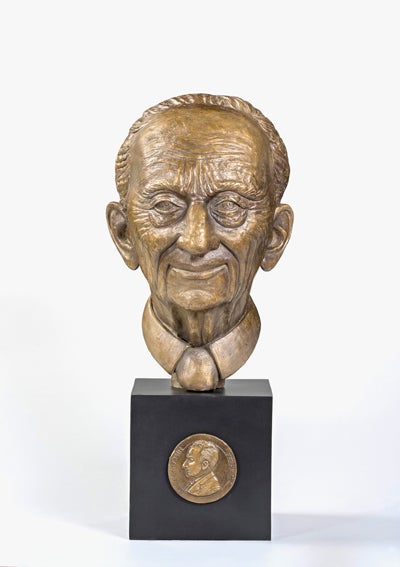

Bjorn Okholm Skaarup is an historian and sculptor, based in New York. He contributes regularly to the Danish weekly Weekendavisen, and has had major public sculpture installations throughout New York City.