July 8, 2020

A committed Christian, Holly Huffnagle first learned that Christianity had fueled centuries of antisemitism while studying abroad in Poland during college. After visiting the Nazi concentration and death camp of Auschwitz-Birkenau, Huffnagle vowed to devote herself to stopping the spread of Jew-hatred.

She has honored that pledge. After five years at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum as a researcher, she served as the policy advisor to the Special Envoy to Monitor and Combat Antisemitism at the U.S. Department of State. Her expertise in fighting antisemitism in Europe and around the world have equipped her to fight the problem here at home.

Now AJC’s first U.S. Director for Combating Antisemitism, Huffnagle tackles multiple sources of Jew hatred every day, including white supremacy, far-left anti-Zionism, and Islamist extremism.

Her personal background as an evangelical Christian with Southern roots has enabled her to show the world that Jew hatred is a social ill that cannot be mended by Jews alone.

“Most non-Jews in America, when they think of antisemitism at all, see it as a Jewish issue for Jews to solve,” she says. “I disagree. It’s a societal issue.”

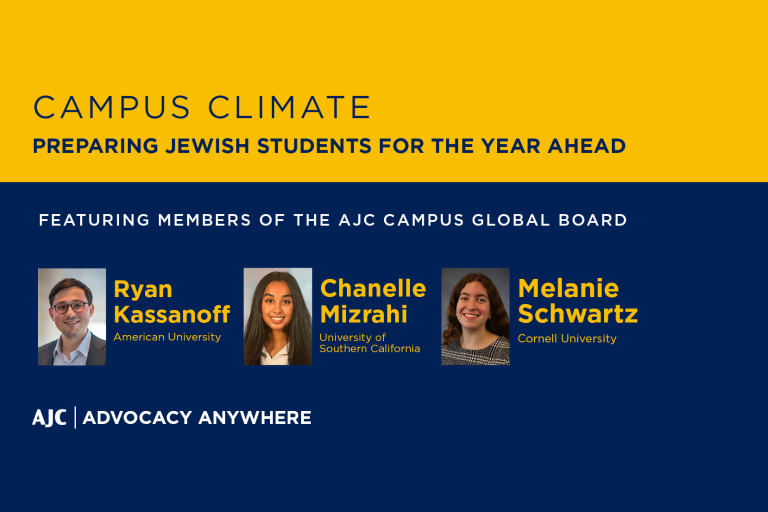

Since assuming the role in April, in the middle of the global pandemic, Huffnagle has hosted virtual webinars as part of AJC’s digital Advocacy Anywhere initiative. The events have ranged from engaging college students on the threats of antisemitism on campus to hosting discussions about the rise of hate speech on social media platforms. She is also leading a task force on AJC’s response to white supremacy.

Raised in Thousand Oaks, California, in the Baptist church co-founded by her maternal grandparents, Huffnagle attended Westmont College, a Christian liberal arts school, in Santa Barbara. During a college semester in Europe in 2007, she studied in Poland, Germany, Austria, and France and first learned about the role Christianity had played in the centuries of persecution that led to the Holocaust.

Fathers of Christianity – St. Augustine, Thomas Aquinas, Martin Luther – had always been presented as exemplary faith leaders, she said. She’d never known they espoused varying levels of antisemitism.

“What changed for me at Auschwitz was a realization of my own responsibility and needing to do something about it,” Huffnagle says. “To work to right a past wrong committed in the name of Christianity – that was my entry point to all of this.”

Huffnagle earned her master’s degree at Georgetown University, where she studied twentieth century Polish history, with a focus on Muslim efforts to save Jews during the Holocaust. She lived and worked in Poland to conduct research on ethnic minority relations before World War II and was selected for the Auschwitz Jewish Center fellowship on prewar Jewish life and the Holocaust in Poland and northern Slovakia.

While working at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum’s Mandel Center of Advanced Holocaust Studies in Washington, D.C., “I knew I wanted to pursue this topic, not just of Holocaust remembrance and combating Holocaust denial, but contemporary antisemitism,” Huffnagle recalls. “I wanted to understand why it didn’t end with the Holocaust like it should have.”

During an internship at the U.S. State Department in 2013, she was assigned to work on the preservation of Jewish cemeteries, Holocaust remembrance, and combating antisemitism and historical revisionism in Ukraine, Moldova, and Belarus. There, she met Ira Forman, the newly appointed U.S. Special Envoy for Combating Antisemitism, who tapped her as one of his most trusted advisers.

In 2015, the State Department launched an effort to stop Hungary from erecting a statue of Balint Homan, a former Hungarian government minister and opponent of communism, who was also a vehement antisemite and called for the deportation of Hungarian Jews during World War II. The statue was part of a campaign to posthumously rehabilitate Homan as a Hungarian patriot.

Forman said Huffnagle made sure the potential clash with the Hungarian government had support from the U.S. embassy and that senior diplomats arrived in Hungary at a crucial moment. Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban eventually condemned the monument.

Huffnagle’s tenure at the State Department demonstrated to her time and again that the key to fighting antisemitism is making sure political leaders understand what is at stake.

“You can teach people what happened in the Holocaust and there will be some students like Holly who will be inherently interested,” Forman says. “But for most students you might as well be talking about the Roman Empire… You have to build up political leadership from the president down to the local city council and make sure our political leaders speak out about this.”

Hungary’s revisionist history was not unlike the revisionism Huffnagle encountered during her academic research in Poland, where many Polish Christians contrasted their own suffering to that of Jews during the Holocaust. The movement to recapture Polish pride under the Law and Justice Party has revived a narrative that effectively absolves those Polish citizens who committed crimes during the Holocaust.

It’s also not unlike the revisionism and complex history she has witnessed firsthand in the American South, where she has grappled with her own family’s past. As a young girl, Huffnagle learned a new name for the Civil War, in which her ancestors had fought for the Confederacy. “I lightheartedly called it the ‘War of Northern Aggression,’ not realizing this title was developed by revisionists of Southern history aimed at preserving the Confederate legacy in a better light,” she recalls.

Later generations of her family fought for civil rights. Before moving from Mississippi to California, her paternal grandfather had saved a black man from being lynched. Her paternal great grandfather risked his life escorting Blacks to the polls to vote in Mississippi.

“But not everyone in my family acted righteously,” she says. While she knows now that the Confederacy fought to defend slavery, not state’s rights, she also grasps that reckoning with the past involves feelings as well as facts.

The recent national movement to remove racist and Confederate symbols from public spaces especially resonates with Huffnagle, whose mother’s relative, James Ewell Brown “Jeb” Stuart, served as a Confederate general. In 2017, a high school in Falls Church, Virginia named for Stuart was renamed Justice High School.

“When your relative’s name is on things – schools or medical centers – you’re usually proud of your namesake,” she says. “Did it make me sad? Did it make me resentful to see Jeb’s name removed? I think it might have if I hadn’t been so exposed in my work to understanding the perspective of others’ pain.”

Huffnagle models a perspective that is vital to fighting antisemitism, Forman says.

“We need allies in other governments and allies in western Europe,” he says. “Beyond that we need civil society, wherever they are. Without civil society we don’t win these battles.”

Forman defines winning the battle as minimizing antisemitism, not erasing it entirely. That’s unrealistic, he says.

Huffnagle hopes that her diplomatic experience overseas, her interfaith work, and her ability to listen and understand others’ points of view enhance her ability to enlist more allies in that battle.

Antisemitism is rising in America, she says, but “the more non-Jews are active in fighting antisemitism, the lower the levels. If we can build trust and broad-sweeping coalitions to tackle the problem together, that’s a win. We have come a long way in our history, but we still have a long way to go.”