February 14, 2018 — Paris

This piece originally appeared in Times of Israel (French edition).

“Every time that one of our citizens is assaulted on the streets due to his age, appearance, or religion, it is an attack on the country as a whole. Today especially, we stand united with the French Jews, and together we will fight every one of these vile acts.”

These words were uttered by French President Emmanuel Macron following a violent antisemitic attack committed by two teenagers on an eight-year-old boy on the streets of Sarcelles.

President Macron's words demonstrate a growing awareness of this scourge at the highest levels of government and a determination to take a stand. So why is it that despite such admirable statements I feel a disheartening and wearying déjà vu?

This antisemitic outrage is just the latest in a long list of attacks against Jews over the last two decades. While antisemitic violence has been on the rise for a long time, just recently we went from 77 violent acts in 2016 to 97 in 2017, an increase that the Minister of the Interior has called "troubling."

Antisemitic crimes have been going on for so long that they are now commonplace, and the same questions are being repeated at each new outbreak, to no avail. What more can we really do? How can we better fight this scourge? Things will not get better with strong statements alone, no matter how significant and heartwarming they are. We must face the fact that we have reached a point of no return unless France adopts a clear, coherent zero-tolerance policy.

As the “broken glass” theory of crime prevention demonstrates, delaying the repair of a single broken window triggers a vicious cycle, generating further violence and incivility. Besides the significance of the act itself, it also feeds insecurity and encourages delinquents to commit more serious acts. It is therefore essential to deal with problem as quickly as possible—to repair our windows before the problem escalates.

So, what does zero-tolerance mean in the face of antisemitism? It means that we must no longer hesitate to decry even the smallest antisemitic incident. On the contrary—as soon as the first insults, incidents, or aggressions take place, we must decisively condemn them. Antisemitic demonstrations disguised as anti-Israel protests should no longer be met with indifference and their vile slogans must no longer escape criticism. And surely the publication of material calling for the murder of Jews should not be up for discussion!

The young boy’s attackers in Sarcelles were 15 years old. At that age, they had already studied 20th-century history in middle school, had already learned about Germany in the 1930s, and had doubtless covered the Holocaust itself. If, notwithstanding their education, they had so much hate inside them to assault an eight-year-old boy for being Jewish, their school system failed to impart the lessons of history, civic values, and pluralism. Indeed, there have been numerous reports of loss of authority in our schools, teachers finding it impossible to raise certain topics in history class, such as the Holocaust. Teachers need support and proper training to deal with these issues. They should be equipped to deconstruct conspiracy theories, prejudice, and religious fundamentalism, and to defend secularism. They need to be able to identify and condemn antisemitism when they see it.

France has one of the strongest legal arsenals against criminal behavior in the world, but much of it is not actually applied. For example, the PHAROS system, used to identify illegal behavior on the internet, is no longer sufficient in an era when antisemitic diatribe has spread across the globe. Social networks such as Twitter and Facebook, and content creators such as Google and its video channel YouTube provide antisemites and racists a platform and de facto impunity. Faced with this new cyber-threat, the rule of law is ill-equipped to uphold our humanistic values, nor can it punish those guilty of infringing upon them quickly or severely enough.

The longer the justice system dithers, the more it undermines itself. The judge presiding in the case of Sarah Halimi, the Jewish woman who was murdered in her house last year, refused to classify her murder as an antisemitic act. What kind of message is the state sending its citizens? The case is clear-cut: Did Halimi’s murderer not call her a “sheitan” (devil in Arabic) as he tortured her? Did he not proceed to throw her out the window shouting “Allah Houakbar?” Had he not threatened her before and insulted her because she was Jewish? The message that this sends to antisemites is frankly unsettling.

And finally, the fight against antisemitism in France is not a uniquely French issue – it is inextricably linked to foreign policy. For years now, Saudi, Turkish, and Qatari money has financed Muslim organizations and mosques in France, facilitating the spread of politicized and extremist views of Islam. There is no transparency and few penalties for the propagandists. The Arab world produces a large part of the content spread by radicals and antisemites (and easily accessible via satellite television and the internet). Several years ago, the European Union introduced the “More for more” initiative, aimed at offering more solid partnerships with countries that logged the most progressive democratic reforms. Putting an end to antisemitic, anti-Christian, and anti-Western discourse by stopping its funding (whether public or private) from countries with dubious motives should be part of a zero-tolerance approach by the EU.

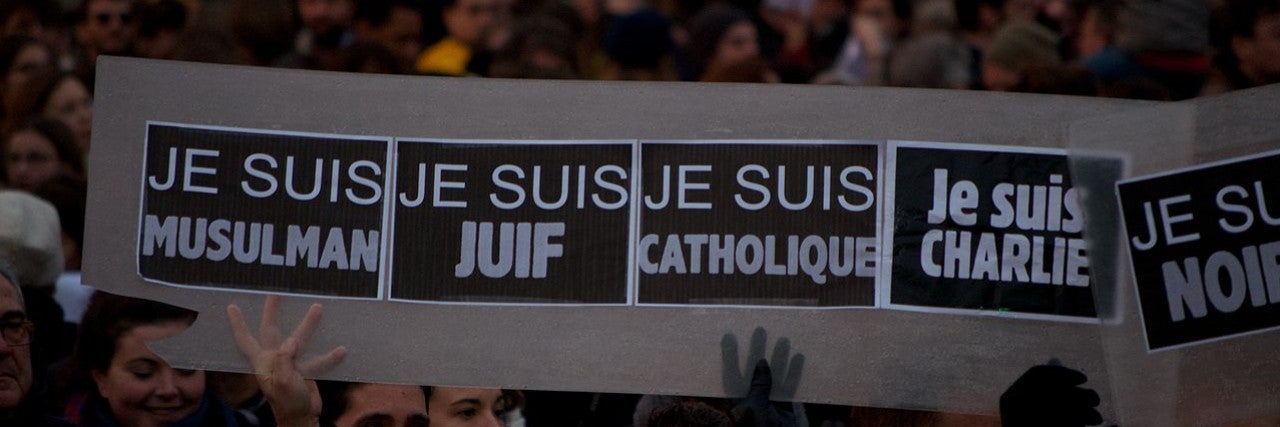

Since antisemitism is symptomatic of a greater societal malaise, the application of a zero-tolerance policy affects not only French Jews, but all of us. The future of French and European values is at stake.

Simone Rodan-Benzaquen is Director of AJC Europe.