April 3, 2019

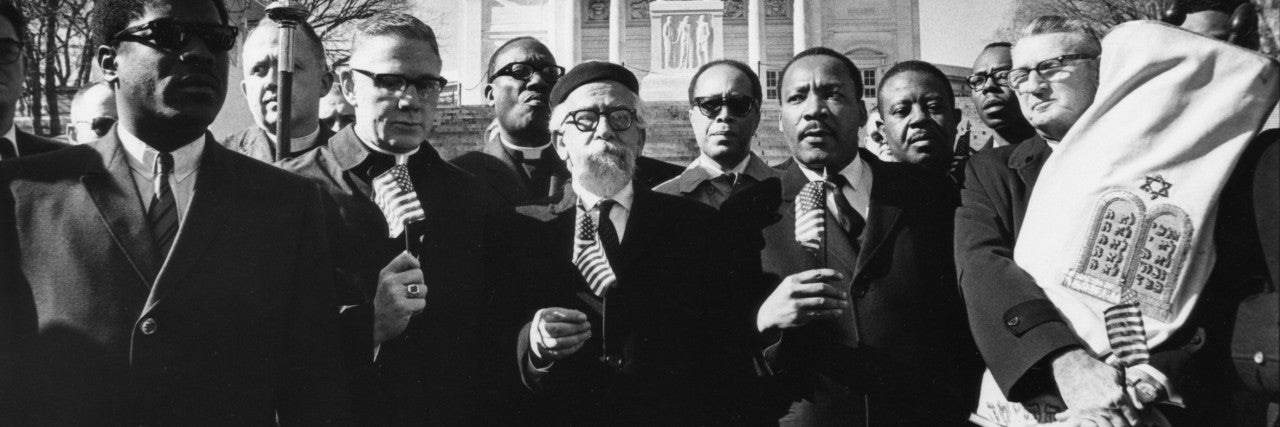

The iconic image of Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel linked arm in arm with civil rights leaders, including Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., sometimes seems to symbolize a bygone era.

Now, 51 years since King’s assassination on April 4, 1968, black and Jewish communities find themselves at a crossroads: facing a common enemy yet struggling to unite around issues that affect each other’s survival.

For many African-Americans, the fight for justice has centered on ending police brutality and the mass incarceration that targets black men. For many Jews, the mission has focused on defining antisemitism and explaining why questioning the existence of Israel poses a threat.

But the white supremacy that has spawned attacks on houses of worship in Charleston, Pittsburgh, and New Zealand threatens both.

“There is a growing sense of white nationalism and if you listen to the people who espouse that, the hatred is really toward immigrants, blacks, and Jews,” said Lonnie Bunch III, founding director of the Smithsonian's National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Bunch recently spoke to AJC on its podcast AJC Passport.

“In many ways it’s really incumbent on us to do some of the work we’ve done in the past, which is to illuminate all the dark corners of the American experience, to make sure people are clear about what these racists stand for.”

“I think this is a real good time for blacks and Jews to say it’s our time again and join hands and fight for a better country.”

It may not be apparent to most, but Black-Jewish partnerships are springing up across the country, said Dov Wilker, Director of AJC Atlanta and AJC'S Director for Black-Jewish relations. “From Los Angeles to Philadelphia and Capitol Hill, AJC is on a mission to resurrect what was once a powerful and effective alliance.

But as more African-Americans successfully run for city halls, state legislatures, Congress, and the White House, and more local and national government officials voice concerns about Israel, engagement has shifted from religious and civic spheres to the political arena.

In Washington D.C., AJC has been working with U.S. Rep. Brenda Lawrence of Michigan to develop a Black-Jewish Caucus to bring together politicians from both communities to learn from each other and advocate for joint concerns.

Listen to AJC Passport

While the idea of a Black-Jewish caucus developed long before, the tension that boiled over last month when Minnesota Congresswoman Ilhan Omar posted antisemitic remarks to Twitter underscored the need for such a group. While many Jews couldn’t understand why some political figures didn’t grasp the bigoted undertones of Omar’s tweets, some in the African-American community felt the level of attention paid to her remarks was excessive and wondered if race placed a role.

But repeated slights and clashes over the last few decades already had eroded the relationship. In the early 1980s, U.S. presidential candidate Jesse Jackson gave an interview in which he referred to Jews as “hymies,” a derogatory term.

In the early 1990s, an African-American child was killed and another injured when they were struck by a car in the motorcade of Chabad leader Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson. The tragedy sparked deadly riots in Crown Heights, Brooklyn. More recently, in 2016, a coalition of groups affiliated with the Black Lives Matter movement issued a platform that demanded sanctions against Israel, which it called an “apartheid state.”

Julie Rayman, AJC Director of Political Outreach, said the Black-Jewish Caucus will seek to address a sentiment in both communities that the leaders of the other are not with them.

“Every community comes with their own sensitivities,” Rayman said. “We’re going to arm them with the best information they can get about our sensitivities. Then with our listening ear we will ask: ‘What are yours?’"

Wilker said both communities need to have candid conversations about what constitutes antisemitism.

“We, the Jewish community, haven’t done a good enough job of educating people on what antisemitism is,” Wilker said. “There’s a difference between criticizing Israel and using Israel as a ploy to cover your antisemitism.”

He points to Hank Johnson, a Georgia congressman who in 2016 compared Jewish settlers on the West Bank to “termites,” evoking the Nazi portrayal of Jews as vermin. Wilker said Johnson simply did not know he had uttered an antisemitic trope. When it was brought to his attention, he apologized profusely. The Caucus, and its attempts to proactively educate about antisemitism will go a long way toward preventing such missteps, Wilker said

The formation of the Caucus is a chance to teach those lessons, as well as amplify advocacy for voting rights and tougher hate crimes legislation, Rayman said.

Bunch said leaders must agree to disagree on some issues so they can coalesce around others.

“What’s really important is that we support each other in a way that says the African-American and Jewish community do not have to be in lockstep on every issue,” Bunch said. “We can debate a variety of issues, but we shouldn’t let those debates be the splinter that separates us. Because ultimately our greatest strength is in unity and if we allow the right to have legitimate debate to prevent us from moving forward then I think we’re playing into the hands of the neo-Nazis.”